Plot As a child Bruce Banner is genetically altered by the experiments of his father and is orphaned when his mother is murdered by his father and the project is shut down by the military. As a man Bruce Banner (Eric Bana) is a mild mannered scientist researching ‘nanomed’ technology and gamma radiation, he lives an unfulfilled life secretly pining after his co-worker Betty Ross. However, Bruce’s own troubled past and introverted personality cause him to be distant and thus pushed around by both a government defence contractor looking to apply his research to modern warfare and Betty’s father, a US military General, who has a deep mistrust of Bruce. Unbeknownst to Bruce his estranged father, David Banner, has also begun working secretly at his research facility. After an accident at his laboratory he begins to transform uncontrollably into a green monster whenever he becomes enraged. Bruce is imprisoned in his own home by Talbot and General Ross after transforming for the first time but breaks free and saves Betty from the mutated animals sent by his father to kill her. Betty cares for Bruce but he is tranquilized and taken to a military facility the next day by the General. David Banner then breaks into Bruce’s laboratory and subjects himself to gamma radiation in order to mutate himself, which he does, allowing him to absorb matter into his body by touching it. He is experimented upon by the military and by Talbot in order to extract and weaponize his DNA; the plan goes wrong, however, and the Hulk overpowers the facility’s defences to break free. The Hulk bounds across the desert, destroying all military vehicles sent to attack him, and ends up in San Francisco where he is finally calmed back to a human state by Betty. Bruce is then taken to another military facility where his father goes to see him. When Bruce refuses to join forces with him, his father transforms and attempts to destroy Bruce and absorb his powers. However,the power of the Hulk proves too much for his father to bear and he swells to an enormous and uncontrollable mass that is then destroyed by a bomb that General Ross drops on the two. Bruce is presumed dead after the explosion but a coda shows him in South America attempting to help others and control his power.

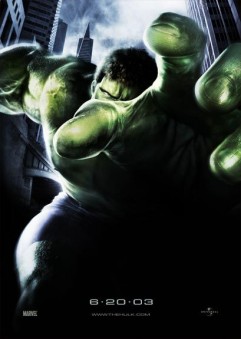

Film note On the eve of the release of Hulk in the summer of 2003, Ang Lee was anxious that his $150m film would not hit the blockbuster box-office targets demanded by the studio. According to Dinning and O’Hara, Lee stated, “I hope it hits every mark of a summer blockbuster […] I hope as much as the studio does that it has playability. They will sell the hell out of it in its first weekend, but after that it remains to be tested” (qtd. in Dinning and O’Hara 1). Unfortunately for Lee, his worst fears were realized: as Dinning and O’Hara note, “[Lee’s] challenging take on a traditional summer formula broke the record for a June opening with its three day $62.1m take, but the following weekend box-office receipts fell an almighty 70 per cent. The film’s three weekend total of $117m may have been impressive five years ago, but today, with event movies regularly costing $100m-$200m to produce and at least $50m to release in the domestic market, a 17-day gross of $117m is considered disappointing” (1). Indeed, the dramatic failure of Hulk at the box office had a colossal effect on the Taiwanese filmmaker, which according to Minnihan almost led him to end his career: “After three exhausting years spent making a Hollywood film that under-performed at the box office, Lee almost retired”. So why was there such a poor reception for a film that, from the outset, appeared to have all the credentials to make it a runaway success?

Superhero saturation Lou Lumenick of The New York Post claimed “It’s clear the public is wearying of the incessant string of blockbusters rolling off the assembly line” (qtd. in Dinning and O’Hara 1) and Patrick Goldstein of The Los Angeles Times added “It’s a pretty scary proposition but is it possible that the average 16 year old has better taste in movies than most of the rich, Ivy league-educated studio executives who have flooded us with a deluge of movie sequels this summer?” (qtd. in Dinning and O’Hara 1). To further complicate matters, Fox international theatrical president Scott Neeson pointed to problems with exporting US films overseas: “We used to have a much more extended play period going into October but now the blockbusters are opening week after week in foreign territories and falling off much quicker than they used to” (qtd. in Dinning and O’Hara 2). Clearly, Hulk’s struggle at the box office can be attributed to the method of distribution and release within the wider context of an over-saturation of blockbuster films, but as some critics have pointed out the film itself failed on several counts to live up to expectations.

Janet Wasko notes that “during summer 2002, teasers for The Hulk were shown, although the film was not scheduled to open until summer 2003” (197). Many believe these teasers ruined the project from the beginning. As Dinning and O’Hara point out: “You will no doubt remember the brouhaha on release about the film’s effects–lampooned as they were around the world when Hulk ruined halftime at the Super Bowl by chucking around some tanks in his unconvincing stretchy pants” (160). In addition a number of work-prints of the film were leaked online at a crucial stage just before the film’s release and the build-up to the film was marred further “as fans eviscerated what the studio claimed were unfinished special effects” (Mancini). Moreover, Roger Ebert, a rare champion of the film, also points to the special effects as being a crucial weakness in the film when he says that “the Hulk himself is the least successful element in the film. He’s convincing in close-up but sort of jerky in long shot–oddly, just like his spiritual cousin, King Kong” (2003). Clearly, the painstaking work by the crew at Lucas’ Industrial Light and Magic had failed to hit the mark.

Moreover, plenty of reviews criticized the film’s lack of action. Dinning explains that “in reality, so defensive is Mr Lee of his hero that he analyses and anaesthetizes him into impotence. All the oedipal wittering leaves precious little time for fun” (160). Peter Bradshaw echoes these sentiments when he claims “Hulk is long-winded, dull and ill-conceived […] Bounding across the Nevada desert, our hero resembles a rubber breakfast-cereal freebie on a pogo stick–and this is as fun as the film gets” (488). Mark Kermode concurs, describing the film as “[a]n ill-fitting blend of serious psycho drama and jolly-green-giant jumping around”. He ridiculed the film’s tag-line, rewriting it, “You wouldn’t like me when I’m Ang Lee!”.

However, while the film’s lack of fit with the wider superhero genre (prominence of psychological realism, interest in character development, serious allegorical dimension and so on) was read by critics as a shortcoming (and an explanation of poor box office), the film can be judged on its own merits. For example, the film’s bravura opening sequence signals the complex temporal structure of the film: a montage shows David Banner experimenting before his son’s birth, images of Bruce’s childhood, and Bruce’s position in the present; a series of images that develop back-story whilst establishing the sense of continuous temporal disparity and trauma that will haunt the film’s narrative and its characters. In one particularly clever scene, Bruce enters a photograph and stands next to Betty, at which point we realize this is a flashback, only for Betty to describe a dream which is also visualized, involving another flashback of her witnessing the green flash of the atomic bomb, and then her imagined strangulation at the hands of Bruce. By placing this exterior analepsis within an interior (interior) analepsis, Lee manipulates the temporal shifts with apparent effortlessness and simplicity, yet the implications are complex and profound. What appear to be flashbacks, memories of the past, are perhaps better understood as representing the traumatized psyche of the present and the breakdown of that most precious US institution: the nuclear family. In addition, Lee incorporates diverse and experimental styles of editing something acknowledged by Ebert: “The movie has an elegant visual strategy; after countless directors have failed Ang Lee figures out how split-screen techniques can be made to work. Usually they’re an annoying gimmick, but here he uses moving frame-lines and pictures within pictures to suggest the dynamic storytelling techniques of comic books” (2003). That audiences and (the majority of) reviewers didn’t relish this complexity doesn’t make it any less distinctive and artistic. Indeed, Lee’s failure (if that’s the right word) was to create an almost Hitchcockian superhero, rich in psychological complexity in a film replete with rich symbolism and clever mise-en-scene. Perhaps it is no accident that Danny Elfman’s score was based on Bernard Herrman’s score for Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), with both films located in and around San Francisco.

Shadow archetypes Hulk did have its supporters, however, with Ebert claiming “The Ang Lee film was rather brilliant in the way it turned the Hulk story into matching sets of parent-child conflicts” (2010 207), and Sight and Sound featured it as its film of the month in August 2003, where Rob White claimed it to be “in another league of complexity and for this reason is the best Marvel adaptation so far”; adding “Lee’s career is fast becoming the most interesting in Hollywood”. Yet perhaps the most important critical response for Lee was that of his father. According to Minnihan, “Upon seeing Hulk, Lee’s father for the first time approved of his career as a filmmaker”. Problems with parentage are central to the superhero genre. The absence of parents seems to highlight the lonely plight of the hero, leaving them vulnerable and often emotionally traumatized. Indeed, Peter Parker is raised by his aunt and uncle in Spider-Man (2002); Bruce Wayne is orphaned from a young age when his parents are gunned down by Jack Napier in Batman (1989), and his butler Alfred proves the closest thing he has to a parent throughout the franchise; Hellboy is summoned from hell parentless, an orphan even before he enters the world; Clark Kent is raised by adoptive parents after his mother and father are left to perish on his home planet Krypton in Superman (1978). Even the private academy in the X-men trilogy serves as a kind of orphanage, housing the unwanted ‘freaks’ of society whose own parents have turned their backs on them. The comic strips these films are based on are clearly targeted at teenage boys who, whilst experiencing adolescence, will likely relate to the problems and issues of parentage (or lack of) that exist within the genre, and threaten the grand ideal of the American family. If anything in Hulk, director Ang Lee has taken the issue of parenting and patriarchy within the superhero film to the next level.

In an article for the journal, Asian Cinema, Kenneth Nordin suggests that both Hulk and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon “fit beautifully into the framework of Jung’s theory of the shadow/ego archetype. From a Jungian perspective, both Yu Jen and Bruce Banner are embarked on heroic journeys to free themselves from dark, parental influences. Jung describes this inner struggle to be free and whole as the process of individuation” (121). Indeed, Yu Jen’s struggle with her ‘shadow-self’ in the form of Jade Fox mirrors Banner’s battle with his darker inner-self, the Hulk, whereby both characters seek individuality and maturity. Interestingly, Nordin states that “[t]he color green, according to Jung, symbolizes the psyche’s unconsciousness in which the shadow archetype begins to take form before manifesting itself in conscious experience” (123). Yu Jen’s journey of emotional and spiritual development is triggered by her obtainment of the “Green Destiny”, an ancient sword that seemingly brings about her flight to maturity. Indeed, for Nordin, the fact that “many of her swordfights take place off the ground–on roof tops, on the second floor of a wayside inn, and finally in wind-blown green treetops” alludes to the spiritual nature of her plight brought about chiefly by her possession of the sword (125). These flights of spiritual fancy may be contrasted with Hulk’s giant leaps across the rocky desert and his fight amongst the treetops with the mutant dogs. Moreover, Nordin notes “[t]he emergence of green snakes or dragons in dreams or myths, Jung said, represented the emergence of the shadow archetype out of the conscious state into the conscious half of the psyche.” (123). This assertion takes on particular relevance if we consider the young Bruce playing with his favourite toy, a stuffed green dragon, which is filmed in jerky fast-motion as it attacks: this premonition of events later in the film highlights the fact that due to his father’s reckless experiments, Bruce, like the mutants in X Men and Hellboy “was born a genetically altered human being” (Nordin 129).

The conflict between Bruce and his shadow-self is set up early on by Lee’s use of the mirror. We are introduced to Bruce as he shaves, and the flicker of green in the close-up of his eyeball is our first acknowledgement of the monster within him. As Hulk smashes through the mirror and throttles Bruce, he utters his only clearly spoken words of the film: “Puny Human.” As Homer suggests “[t]he reflected image presents a dilemma for the infant because it is at once intimately connected to its own sense of self and at the same time external to it” (31). This scene is paramount to our understanding of Bruce’s inner-struggle, and is the only time the two counterparts of his personality–the introvert scientist and the raging Hulk–meet on a physical level.

The scene’s importance is strengthened further by the repetition of the motif of reflective surfaces, especially the repeated imagery of water. Having saved Betty from the pack of mutant dogs, Hulk gazes despairingly into a small lake at his own reflection until he gradually transforms back to Banner. At the end of the film, Hulk gazes into Pear Lake and sees his reflection to be that of his father at the time of Bruce’s childhood. Hulk’s instinctive lashing out at the image highlights the view expressed in an article titled ‘Not just the quiet man’ in The Observer that “In Lee’s rendering, the unleashed alter ego becomes a darkly Freudian tale, part Oedipus and part Frankenstein. Central to this interpretation is the role, played by Nick Nolte, of the father who aims to exercise a godlike control of his son. Indeed, the ultimate battle between father and son that immediately follows can certainly be related to the Lacanian assertion noted by Homer that “the imaginary is a realm of identification and mirror-reflection; a realm of distortion and illusion. It is a realm in which a futile struggle takes place on the part of the ego to once more attain an imaginary unity and coherence” (31). As Bruce lies submerged in a state of dreamlike oblivion remembering fondly his younger self receiving a caress from his father after the nuking of the lake, this element of “unity and coherence” is suggested for the first time, with his father’s softly spoken words “sweet dreams” implying some closure to the trauma and repression he has suffered because of his patriarchal oppressor.

Hulk as war allegory The lengthy sequence where the Hulk is pursued across the desert and through San Francisco may at first glance portray the idea put forward by King, whereby “Hollywood action movies are relatively free to indulge in all sorts of death and destruction […] without any great concern about issues of historical veracity or responsibility” (118). However, there are deeper allegorical meanings at play, and as Holloway notes “[i]n Hollywood allegory lite, controversial issues can be safely addressed because they must be ‘read off’ other stories by the viewer; while the ‘allegory’ is sufficiently loose or ‘lite‘, and the other attractions on offer are sufficiently compelling or diverse, that viewers can enjoy the film without needing to engage at all with the risky ‘other story’ it tells” (83). In this sense, elements of Hulk certainly lend themselves to be read as an “allegory lite” of America’s war on terror. As Hulk is chased through the desert and across the rocky landscape, Elfman’s music turns unmistakably Middle-Eastern in style. The combination of visual and audio tracks leaves no doubt as to the intended metaphor, and the constant barrage of missiles, bullets and heavy duty artillery by the trigger-happy general and his army seems to reflect perfectly the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. As with the insurgency in these countries, military intervention actually increases the Hulk’s power. The film’s anti-war message is stated baldly in David Banner’s angry speech during his confrontation with his son in the aircraft hanger: “Think about all those men out there in their uniforms! Barking and swallowing orders! Inflicting their petty rule over the entire globe! Look at all the harm they’ve done! To you! To me! To humanity! And know this! We don’t need them, and their flags, and their anthems!”.

Moreover, Hulk’s emergence from the ground in San Francisco following his plummet back to earth reflects Holloway’s assertion that in War of the Worlds the “aliens who traditionally arrived from space came instead from underground, present but invisible among us like terrorist sleeper cells” (92). As Hulk resurfaces the road breaks up, trams are brought to a crashing halt, cars pile up and panic ensues in a manner similar to a terrorist attack. This idea is also suggested in the mutant’s skirmish at a train station in X Men, and in Hellboy, whereby the “hero” crashes through a subway station whilst exchanging blows with a hideous mutated creature. These films have picked extremely vulnerable and public locations to stage their intense action sequences; locations that have historically been the target of terrorist attacks. This clever play with the comic’s subtexts is another aspect of distinction in this superhero adaptation. Indeed, it may be the case that Lee’s clever filmmaking and desire to find ways to make his narrative resonate with audiences – things to celebrate – may well have been the very elements that resulted in the film’s poor box-office take.

References

Bradshaw, Nick. ‘Review: Hulk’. Time Out Film Guide. Ed. John Pym. London: Ebury, 2008: 1073. Print.

Dinning, Mark and O’Hara, Helen. “What has Gone Wrong in the US?”. Screen International. 1412 (2003): 1-10. Print.

Ebert, Roger. “Review: Hulk”. Chicago Sun-Times.com. 20 Jun. 2003. Web. 04 May 2010.

___. Roger Ebert’s Movie Yearbook. Missouri: Andrews McMeel, 2010. Print.

Holloway, David. 9/11 and the War on Terror. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2008. Print.

Homer, Sean. Jacques Lacan. Abingdon: Routledge, 2005. Print.

King, Geoff. Spectacular Narratives: Hollywood in the Age of the Blockbuster. London: I.B. Tauris, 2000. Print.

Kermode, Mark. “Review: The Incredible Hulk”. Guardian.co.uk. 19 Oct. 2008. Web. 04 May 2010.

Mancini, Robert. “Hulk: Smashing First Impressions”. MTV.com. Web. 04 May 2010.

Minnihan, David. “Ang Lee”. Senses of Cinema.com. n.d. Web. [03 May 2010.

Nordin, Kenneth D. “Shadow Archetypes in Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and The Hulk: A Jungian Perspective.” Asian Cinema. 15.2 (2004): 121-132. Print.

“Not just the quiet man “. Guardian.co.uk. 6 Jul. 2003. Web. 1 Feb. 2010.

Ryan, Michael and Kellner, Douglas. Camera Politica: The Politics and Ideology of Contemporary American Film. Bloomington, IA: Indiana University Press, 1990. Print.

Wasko, Janet. How Hollywood Works. London: Sage, 2003. Print.

White, Rob. “The Rage of Innocence”. Sight and Sound.com. Aug. 2003. Web. 10 May 2010.

Written by David Jones (2010); edited by Mark Birrell (2012), Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2010 David Jones/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post