The Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) is a film festival that is held every year in Toronto, Canada and lasts for 11 days in early September (Fig. 1). It was founded in 1976 by Canadian film producers Bill Marshall, Dusty Cohl, and Henk Van der Kolk and began as a collection of the best regarded films from film festivals across the world. Van der Kolk says that “We thought making a festival would be a way of giving us the kind of profile internationally and locally that would let us make movies” (Goffin). The first festival attracted just 35,000 people but these numbers soon grew and TIFF is now the most popular film festival in North America, being part of the Big Five (the others are Venice, Sundance, Cannes and Berlin) of the most prestigious in the world (Roxborough). It is deemed more popular than Sundance, the only other North American festival that is part of the “Big Five” due to it’s higher attendance, stronger capacity for generating Oscar Buzz and premiering highly anticipated movies. Geographically, the festival takes place in the most populated city in Canada, which is also very well connected to the rest of world with cheap and extensive flights, and as a result of this it manages to combine a large local as well as global audience. TIFF is a charitable trust with ticket sales and memberships contributing 39 per cent of revenues. Its administrative costs are 13% of revenues, and its fundraising costs are 23% of donations. For every $1 donated to the charity, 64 cents go to its two learning programs (Tetzlaf). TIFF tries to promote Canadian film making as well as the film industry in general with awards for Canadian films and functions as an advert for the industry. TIFF is among the festivals that do not limit by genre, instead choosing to split films into specific categories such as Contemporary World Cinemas, Midnight Madness (genre films), Discovery (a director’s first or second feature), Gala Presentations, and Special Presentations. There are prizes for these sub-categories, with the main prize being the People’s Choice Award, a “Best Film” prize that is decided by an audience voting system.

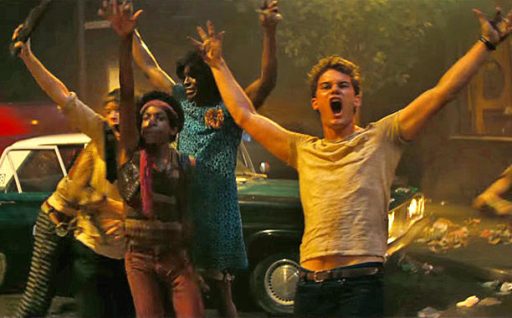

In recent years, TIFF has increasingly hosted premieres of films that have been nominated for Academy Awards (CBS News), and in the last decade all the films (bar one) that won its People’s Choice Award were either nominated for Best Picture or won Best Picture. In this case, TIFF might be accused of pandering to industry production lines whereby certain cliched formulaic films designed to win Academy Awards are given international exposure. The most recent example of this is Green Book (2018), People’s Choice Award and Best Picture winner that focused on racial reconciliation through an interracial friendship (Morris). That said the festival has sometimes been subversive, including the 2011 Lebanese war drama w halla’ la wayn (Where Do We Go Now?) which won the People’s Choice Award but did not make the shortlist for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Film. It is also noteworthy to mention that films that are made by directors with less critical acclaim are sometimes chosen to premiere at TIFF because they have made a more important film that TIFF thinks deserves a spotlight; for example, when Roland Emmerich of blockbuster entertainment like Independence Day (1996)and White House Down (2013) directed gay true story drama Stonewall (2015) (Fig. 2 )it was screened at TIFF despite Emmerich’s former credentials and the pre-release backlash surrounding its whitewashing (Suhas). On the other hand, the Discovery section of the festival was created to counter act and, to prop up emerging creative figures, but the films they choose to screen do not have the same quality assurance because only filmmakers with one or two films can compete in this section.

The benefit of premiering or just screening films at festivals is that the festival becomes a platform to build anticipation and word of mouth. For example, Hustlers premiered at TIFF on September 7th 2019 to very positive reviews and an impressive opening weekend gross of $33.2m on release a week later. Whilst it might have made money regardless, a strong positive reception will increase the chances of audiences wanting to see it. This is made more likely in TIFF’s case because compared to other prominent film festivals the audience vote for the best film screened rather than a jury of industry people. Even where a film is not well received by the audience and critics, this can be turned into a positive. The festival experience can be used as a test screening and the director can then re-edit the film for its release if the reception is unfavourable. Recent examples include Roman J Israel ESQ. (2017) and Outlaw King (2018) (Fig. 3), which both had re-edits for their releases after poor showings at TIFF and had better receptions as a result.

There have been controversies along the way. In 2009, for example, TIFF programmers decided to screen ten Israeli films as part of their line-up. The problem was that this was during the Israel-Palestine conflict, with the festival taking place less than a year after Israel’s invasion of Gaza. As a consequence TIFF were seen as promoting propaganda on Israel’s behalf and this sparked protest and division, with some (including director Ken Loach and writer Fredric Jameson) signing a petition criticising TIFF and others (including producer Robert Santos and documentary filmmaker Simcha Jacobovici) defending the festival. TIFF did not prevent the films from screening, but have subsequently adopted a very apolitical stance and avoided controversy (Archibald 274).

Gatekeeping is a problem with TIFF, despite the wide range of films shown, the smaller and more independent films that are chosen to be screened often end up being lost in the shuffle in favour of those with large marketing budgets. Girish Shambu laments that although TIFF “still screens a healthy number of worthwhile films […] the more visible, “commercial” tier of the festival tends to drown out discussion of more “marginal films” (qtd. in Porton). In 2017, TIFF even reduced the amount of film screenings to just 255 films rather than the 400 of the previous year, so there is now less of a chance of a film being selected. In 2019, 25 per cent of films billed to be in the gala presentation category had already been screened at other festivals and 24 out of 55 films in the special presentation section had already been screened at other festivals. The best way to fix this problem with TIFF would be to not screen films that have already premiered at the other big festivals. Changing this rule would allow the films that are premiering there to garner more attention, whether they be heavily marketed or lesser known. But movies in the latter category are the films that would thrive in the spotlight at TIFF, because it attracts such a large audience that might be interested in the indie productions as well as the larger scale ones.

Ultimately, the purpose of the Toronto International Film Festival is to please audiences that want to see good and interesting films in advance. But for aspiring filmmakers it presents many unintentional roadblocks and does not showcase as much new talent as it could do.

References

CBS News. “Toronto Film Festival: Oscar Buzz Begins.” Cbsnews.com. 19 Sept. 2009. Web. 1 Apr. 2020.

Goffin, Peter. “TIFF Co-Founder Bill Marshall, 77, Remembered as Pioneer of Canadian Film.” Thestar.com, Toronto Star, 1 Jan. 2017. Web. 1 Apr. 2020.

Morris, Wesley. “Why Do the Oscars Keep Falling for Racial Reconciliation Fantasies?” nytimes, The New York Times, 23 Jan. 2019.

Roxborough, Scott. “Berlin Rebooted: Festival Shuffles Lineup, Aims for Recharged Market.” hollywoodreporter, The Hollywood Reporter, 16 Feb. 2020.

Suhas, Maitri. “Here’s Why People Are Mad About ‘Stonewall’.” Bustle, Bustle, 4 Aug. 2015. Web. 1 Apr. 2020.

Archibald, David, and Mitchell Miller. “From Rennes to Toronto: Anatomy of a Boycott.” Screen, 2011, pp. 274–279.

Porton, Richard. “The Toronto International Film Festival at the Crossroads.” Cineaste Magazine – Articles – The Toronto International Film Festival at the Crossroads, Dec. 2010.

Tetzlaff, Stefan. “Toronto International Film Festival.” Charity Intelligence Canada, 27 June 2019,

Written by Robert Stayte (2020); Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright ©2020 Robert Stayte/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post