The history behind the technology used in digital resurrection is long and complex. Perhaps the most important technique is the use of body doubles and superimposition, a combination that has been used mainly to finish films after actors died before shooting was completed. This post-production technique involves overlaying images of the deceased actor’s face onto body doubles, who stood in place of said actor during shooting. The image is then integrated with audio that is produced either by taking lines from unused scenes or splicing audio clips of the deceased actor’s voice together to form new lines; audio tends to be more complicated in this regard, and so many films, particularly the earlier ones, have tended to avoid it. Some of the best-known examples of digital resurrection are Brandon Lee in The Crow (1994), Oliver Reed in Gladiator (2000) and, more recently Paul Walker in Furious 7 (2015). These techniques were also used when completing Carrie Fisher’s scenes in The Rise of Skywalker, alongside unused footage from the previous films in the trilogy.

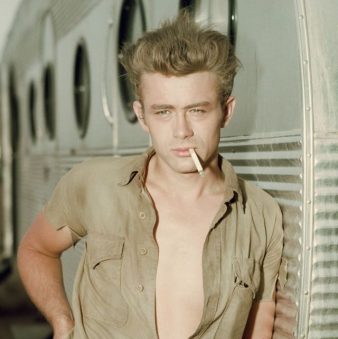

Figure 1

However, in the case of Peter Cushing in Rogue One, the predominant technology used was motion-capture, with actor Guy Henry playing the role (Fig.1). Henry performed Peter Cushing playing Grand Moff Tarkin to create a physical model that was then turned into a digital double; the double was then composited with footage of Cushing and, in a fortunate turn of events, digital mapping based on a three-dimensional life-cast of Cushing’s face made for the 1984 film Top Secret!. The final product has been, as Sargeant states, “universally described with the word ‘uncanny’ – either as praise for its uncannily lifelike quality or as a criticism of its falling in the ‘uncanny valley’” (22). The ‘uncanny valley’ is a term used to describe the creepy and/or off-putting feeling experienced upon seeing human-like animated characters onscreen, as they are only human-like. In Cushing’s case, there are still many of the elements that plague other similar attempts to create digital actors, including a smoothness to the skin that even with added wrinkles and pores still appears plastic-like. There is also a lifelessness to the eyes, which lack the small movements and pupil dilations that are barely perceptible but bring life to a character. However, compared to previous attempts – like the infamous Polar Express (2004) – these are less noticeable, and the performance was described as “breath-taking” as well as “spookily lifelike” (Walsh). It certainly seems that the technology is getting closer to being able to move past this technical hurdle.

While it makes sense to use such technology to complete films where actors have died during production, it is more controversial to cast dead actors into new roles. In Rogue One and the upcoming Finding Jack, one of the questions raised concerns consent. Of course, in cases like Carrie Fisher’s this is more a case of how her image is used rather than it being used at all. Since she had already agreed to be in the film, it was just a case of finishing her last few scenes. However, when it comes to ‘casting’ a deceased actor in a film many years after their death – even in the same film series, as with Cushing – we cannot truly know whether this would be a role they would have chosen to take on.

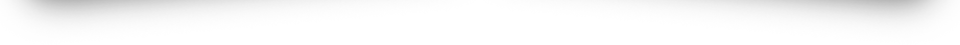

Figure 2

Fame is arguably the greatest driver of likelihood of digital resurrection. While the co-director of Finding Jack, Anton Ernst, has stated that James Dean (Fig.2) is “the right guy for the role, he’s just unfortunately no longer with us” (qtd. in Nolfi), it seems uncontroversial to suggest that Dean’s fame – and the media attention that inevitably followed the announcement of his ‘casting’ – played a role in this decision. This is especially clear with the use of digital resurrection in advertising. Although not technically digital resurrection, there was controversy involving Fred Astaire’s image when a “computer-assisted number with a Dirt Devil [vacuum cleaner] in 1997 was authorised by his widow but led his daughter to say she was ‘saddened that after his wonderful career he was sold to the devil’” (Usborne). More recently, a digitally resurrected Audrey Hepburn appeared in a Galaxy chocolate advertisement, and in China a digitally resurrected Bruce Lee appeared in a Johnny Walker commercial. The latter was controversial because Lee didn’t drink and it is unlikely he would have chosen to endorse this particular product if he were alive. The film industry has countered accusations of commercial opportunism with a claim that bringing certain actors back to life is undertaken for artistic reasons. John Knoll, the chief creative officer at Industrial Light & Magic, has claimed that the Cushing resurrection “was done for very solid and defendable story reasons” (qtd. in Itzkoff). However, even with these defences, it seems that digital resurrection is arguably just an extension of the commercial exploitation of star talent, only no longer restricted to living stars.

Another key issue relates to legal rights. Typically, the consent of the actor’s estate is sought before using these digitally resurrected performers, and though this may appear simple, the legal situation can be complex. Legality centres around, as Tapley and Debruge state, “what’s called postmortem publicity rights, in which the for-profit use of a celebrity’s name, likeness, image, and so on are decided by his or her heirs”. However, whether these post-mortem publicity rights even exist, who they apply to, what they apply to, and many more issues besides still appear to be contentious. In the US, there is currently no federal law related to these questions, and so it varies from state to state. As of 2016, only twenty-three states recognize post-mortem publicity rights (P. Lee and Kahn), and there are huge differences between these states’ laws. The time period in which these rights apply differs, “ranging from 10 years from the date of death in Washington if there was no commercial value at death, to 100 years from the date of death in Indiana and Oklahoma” (P. Lee and Kahn). To whom this right applies is also inconsistent, in terms of the date of death – many states only apply the legislation to those who died after it was enacted – the fame of the deceased party, and their place of residence and/or the state in which their likeness or image is being used (P. Lee and Kahn). California’s statue applies “to individuals who died on or after January 1, 1915” (P. Lee and Kahn), and gives post-mortem publicity rights to the estate of the deceased celebrity for 70 years – an extension from the initial 50 years, obtained after pressure from the Screen Actors Guild (Tapley and Debruge). Other states, such as New York, do not currently recognize post-mortem publicity rights (P. Lee and Kahn); neither does the UK (Tapley and Debruge). In these instances, such as with Peter Cushing, who lived and died in the UK, it seems that getting permission from his estate is more a case of courtesy than anything else.

Who represents these rights, should they exist, is also an increasingly important issue. California-based Worldwide XR is “a new company that aims to bring digital humans to traditional film as well as augmented and virtual reality” (Roettgers). Through a partnership with CMG Worldwide, it owns and represents the publicity rights for over 400 famous figures for whom these publicity rights exist (Roettgers). One of the estates it represents is James Dean’s. However, Alex Lee notes that “after [Dean’s publicity right] expires, the estate, and subsequently Worldwide XR, will lose the rights of publicity. Will it then become a free for all?”. It appears that in many cases it is up to the actors to arrange their own post-mortem publicity protection. Robin Williams famously did this by restricting the use of his name, signature, photograph and likeness for 25 years after his death (Gardner). However, once again, what happens after 25 years is difficult to predict.

Walsh asks “Who gets paid for a digital resuscitee’s role?”. Currently, payment goes to the actor’s estate. Collin notes that “An estimated £2.3 billion is paid in dead celebrities’ appearance fees every year: most goes to the star’s estate, but the rights holders of any source footage will also take a cut”. However, if the actor’s estate holds no legal claim to their digital double, who gets paid? Will the only costs be those of actually producing the recreation? Or will a share go to those who own the source footage from which the doubles are created? There is currently no public information on who or how James Dean’s appearance in Finding Jack will be paid for, nor for Peter Cushing’s appearance in Rogue One, although it may be assumed that since in both cases the actor’s estate was contacted, they were also paid – but this is conjecture.

Figure 3

While it appears that for the most part current users of this technology aim to be respectful to the deceased actors, that does not mean this will always be the case. The potential of this technology may be far more harmful, simply because, as Carver points out, “how each project is handled and whether the image of the deceased is used in a respectful way or not will depend on who is involved in the project”. Although the technology is not perfected yet, it is continually being improved, and these digital doubles may at some point prove more convenient than their living peers; after all, “they show up on time, perform any kind of scene (including pornography) without complaint, they cannot sue, require no rest, and are always available to perform” (Anderson 157). Digital resurrection also links to the ‘deep-fake’ phenomenon, in which videos of famous figures such as Barack Obama (Fig. 3) are altered to allow the editors to make it appear as if the figure is saying anything they want them to – a dangerous development in an era plagued by ‘fake news’. For film one question is more pressing than all others: will there even be a need for ‘real’ actors at all in the future?

References

Anderson, Joel. “What’s Wrong with This Picture – Dead Or Alive: Protecting Actors in the Age of Virtual Reanimation”. Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review, 25.1 (2005): 155-202. Print.

Carver, Meseret. “Resurrecting the Dead and Reversing Aging: Why Actors Are Worried About CGI”, observer.com. 16 Dec. 2019. Web. 26 Mar. 2020.

Collin, Robbie. “First Carrie Fisher, Now James Dean: Why Hollywood Keeps Bringing Stars Back from the Dead”, telegraph.co.uk. 6 Nov. 2019. Web. 26 Mar. 2020.

Gardner, Eriq. “Robin Williams Restricted Exploitation of His Image for 25 Years After Death”, hollywoodreporter.com. 30 Mar. 2015. Web. 27 Mar. 2020.

Itzkoff, Dave. “How ‘Rogue One’ Brought Back Familiar Faces”, nytimes.com. 27 Dec. 2016. Web. 1 Apr. 2020.

Lee, Alex. “The Messy Legal Scrap to Bring Celebrities Back from the Dead”, wired.co.uk. 17 Nov. 2019. Web. 27 Mar. 2020.

Lee, Pou-I and Kahn, Erik. ““Delebs” and Postmortem Right of Publicity”, americanbar.org. Jan./Feb. 2016. Web. 27 Mar. 2020.

Nolfi, Joey. “Finding Jack Director on Digitally Recreating James Dean for Posthumous Movie Role”, ew.com. 6 Nov. 2019. Web. 1 Apr. 2020.

Roettgers, Janko. “Team Behind Digital James Dean Forms New Company to Resurrect Other Legends (EXCLUSIVE)”, variety.com. 12 Nov. 2019. Web. 23 Mar. 2020.

Sargeant, Alexi. “The Undeath of Cinema”. The New Atlantis, 53 (2017): 17-32. Print.

Tapley, Kristopher and Debruge, Peter. ‘’Rogue One’: What Peter Cushing’s Digital Resurrection Means for the Industry”, variety.com. 16 Dec. 2016. Web. 26 Mar. 2020.

Usborne, Simon. “Audrey Hepburn advertise Galaxy chocolate bars? Over her dead body!”, independent.co.uk. 24 Feb. 2013. Web. 1 Apr. 2020.

Walsh, Joseph. “Rogue One: the CGI resurrection of Peter Cushing is thrilling – but is it right?”, theguardian.com. 16 Dec. 2016. Web. 26 Mar. 2020.

Written by Alexandra Kelly (2020); Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Print This Post

Print This Post