Plot The future, in the autocratic society of Panem. Capitol City uses the Hunger Games as an annual means of entertainment and oppression: 24 tributes –a boy and a girl from each of the 12 districts of Panem– are picked by lottery and forced to fight in a televised arena, where the victor is the last one standing. In District 12, Katniss volunteers to take her younger sister’s place in the Games, while Peeta is chosen as her male counterpart. They are taken to Capitol City together with their mentor, Haymitch, a former victor of the Hunger Games, who stresses the importance of sponsors and popularity in order to obtain help to survive in the arena. In a broadcast interview, Peeta reveals his love for Katniss. In the arena, Katniss hides in the woods. The strongest tributes, the Careers, kill most of the others and chase Katniss. The latter, advised by District 11’s young tribute, Rue, drops a nest of poisonous wasps on them as they sleep. Katniss and Rue become allies and destroy the other group’s supplies. When Rue is killed, Katniss places flowers around her body and holds three fingers up to the camera, honouring District 11. Her action triggers the District’s rebellion against the Capitol. A rule change is announced: two tributes can win if they come from the same district. Katniss finds Peeta badly wounded and manages to get medicine for him. Mutant dogs appear into the arena and devour the last Career, Cato, making Katniss and Peeta the last two standing tributes. However, the rule change is withdrawn: only one tribute can survive. As Katniss and Peeta threaten to commit suicide, they are both named victors. While they are taken back home, Snow, President of Panem, reflects on how to respond to their act of defiance.

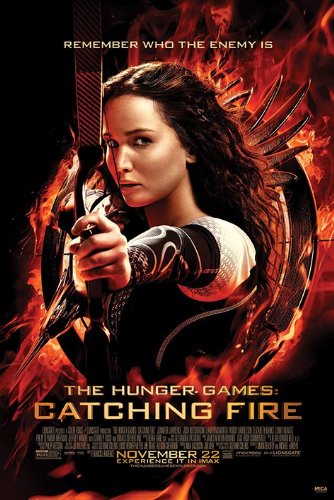

Film Note With a budget of $78m, The Hunger Games grossed $694.4m worldwide, becoming the 20th highest grossing film in North America and the highest grossing film distributed by Lionsgate. The film combines reality TV and violence, indexing feelings of anxiety and political pessimism that can be linked with the context of the War on Terror. A key element in the success of the film is Jennifer Lawrence and her portrayal of a female heroine who reconfigures the gender conventions of the action and Young Adult genres, paving the way for characters such as Tris Prior in Divergent (2014), Imperator Furiosa in Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) and Rey in Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015).

The YA blockbuster In light of the successful adaptations of the Harry Potter and the Twilight Young Adult book series, producer Nina Jacobson secured the rights for Susanne Collins’s The Hunger Games for only $200,000 in 2009, when the novel was just “a promising young-adult book that had sold a hundred and some thousand copies” (Fernandez). At the time, Young Adult fiction was gaining popularity, as indicated by an astonishing 120% increase in the number of titles published between 2002 and 2012 (Whitford and Vineyard). Within this literary trend, The Hunger Games books sold 65m copies in the US alone, and re-launched the dystopian fiction genre, which had not been as successful since the 1960s. While early dystopian novels –such as Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) and George Orwell’s 1984 (1949)– reflected on the loss of freedoms dictated by communism, fascism and World War II, contemporary dystopian fiction is shaped by events such as 9/11 and the War on Terror (Kowalczyk), and the way these are often perceived through the lens of pop culture and reality TV.

According to Laura Miller, the success of Young Adult dystopian fiction is not determined by its portrayal of something terrible that might happen, but rather of “what’s happening, right this minute, in the stormy psyche of the adolescent reader”. The success of The Hunger Games, as Miller points out, is explained by the fact that the Games embody “a fever-dream allegory of the adolescent social experience”, which is characterised by a “brutal social hierarchy” and a lack of comprehension by authoritarian adults. A peculiar contradiction of adolescence is noted by Catherine Driscoll in Teen Film: A Critical Introduction, who writes that the teen film depicts the “adolescent experience” as “both passionate consumption and rejection of conformity, […] both rebellion and gullibility” (4-5). The original trailer for The Hunger Games mirrors both Miller’s and Driscoll’s considerations, since in order to appeal to a young audience it does not highlight any of the larger political implications of the Games, focusing instead on the difficulties of living in District 12, the Reaping, Katniss’s sacrifice for her sister and the training in the Capitol.

The success of Young Adult fiction played a significant role in the marketing of The Hunger Games. In fact, as Geoff King points out, blockbusters are usually “pre-sold, based on properties already familiar to a potential audience” (50). Because of this, book series provide good platforms for successful franchises, which “are planned and packaged to distribute entertainment around the world in as many ways and forms as possible” (Jess-Cooke 7). The marketing of The Hunger Games managed to reach the fan base of the books over a year before the film’s release. With a marketing budget of $45m, Lionsgate promoted the film not only through traditional forms, such as posters and TV commercials, but most importantly through a successful viral marketing campaign that exploited the internet and social media. Viral marketing, a strategy firstly employed with the horror The Blair Witch Project (1999), was successfully systematized by Lionsgate, which used Facebook, Twitter and hashtags, besides creating the website TheCapitol.pn, where fans could register for districts, and even enjoy a virtual tour of the Capitol. This diversified marketing strategy proved effective, and The Hunger Games made the largest worldwide opening weekend for a film not released during the holiday period, with an immediate domestic gross of $152.5m.

With its commercial success The Hunger Games seemed to demonstrate that, because of their broad appeal, Young Adult dystopian books could profitably translate into blockbusters. However, films that followed, such as Ender’s Game (2013), Divergent (2014), The Maze Runner (2014) and The Giver (2014), largely underperformed. Ender’s Game, for instance –with a budget of over $100m and an A-list cast that included Harrison Ford, Ben Kingsley and Viola Davis– was a complete flop, grossing a mere $61m in the US. Maze Runner and The Giver had budgets of respectively $34m and $25m and did not gross more than $102m and $45m. Finally, Divergent, which was expected to become the new Hunger Games, with a budget of $85m, a strong presence on Facebook and Twitter, in addition to “the largest ever pre-release Instagram following for a movie” (Bauckhage), only grossed $150m in the US. The negative reviews and commercial flop of the last Young Adult film released in 2015, Equals, a dystopian story starring Kristen Stewart, determined, according to Ben Child, the death of the Young Adult genre in Hollywood.

“The world will be watching” The Hunger Games tagline (“the world will be watching”) foregrounds spectacle as one of its main features, hinting at the film’s socio-political dimension. The broadcast nature of the Games and their violence mirrors the spectacularization of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, as the author Suzanne Collins suggests when asked about inspiration for the books: “I found myself going in between reality television programs and footage of the Iraq War and these images sort of began to melt together in my mind in a very unsettling way”. Even the name of the dystopian world created by Collins carries a historically loaded meaning: Panem in fact alludes to the Latin formula “panem et circenses” (“bread and circuses”), forms of distraction used by Roman Emperors to appease the masses and secure political consensus.

In addition to the violent Games as spectacular entertainment, the dissemination of war images as a deterrent to political protest is another significant element of the film, which reflects on the use of propaganda in the US during the War on Terror. Nancy Snow observes how the use of the word propaganda in the US is regarded as problematic because of its connotation as “inherently deceitful and thus morally repugnant to democracy-loving people who value the truth over the big lie” (98). However, the widespread idea that democracies do not employ propaganda is a myth, since “the US as the leading democratic republic is also the world’s largest producer and consumer of propaganda” (Snow 98). In The Hunger Games, the Capitol broadcasts a propaganda film at the beginning of the Reaping to justify the Games as atonement for past acts of rebellion as well as a line of defense against new possible crimes, in a way akin to the American legitimization of torture and war after the 9/11 attacks. Editing plays a key role in the manipulation of meaning within the pre-Reaping propaganda film: the past rebellion of the Districts is associated with images of bombs, crying mothers and soldiers dying in battle, as the voice of President Snow reads “widows, orphans, a motherless child”. The crudity of these images is then juxtaposed with the new order established by the Capitol, which is described by President Snow as “peace, hard fought, sorely won”, and linked to images of golden corn fields and a father laughing with his child. At the same time however, the cinematography contrasts the manufactured images of the propaganda film with the misery of the citizens of District 12 who are forced to watch it, surrounded by armed ‘Peacekeepers’ sent from the Capitol.

Not only does The Hunger Games reflect on how images and technologies can reinforce the status quo, it also shows how they can challenge it. In a key scene, Katniss covers Rue’s dead body with flowers and then holds three fingers up to the camera as a mark of respect, aware that her act of defiance is being broadcast live to the districts. Similarly, at the end of the Games, when Katniss and Peeta threaten to commit suicide by eating poisonous berries, thereby short-circuiting the dog-eat-dog logic of the spectacle, President Snow punishes the Head Gamemaker for failing to prevent such a televised act of defiance. The problematic diffusion of these images within the film recalls the Abu Ghraib scandal, and how it challenged the recurrent motifs and routinized scenarios (Kennedy 267) of the war that had until that moment dominated US news. The 1800 images made public by CBS news in 2004 “visualized the War on Terror as a spectacle of bodies stripped of rights and liberties and positioned the viewer as a complicit audience whose gaze reinforces the terror” (Kennedy 269). In the same way, Internet blogs such as crisispictures.org challenged the US circulation of standardized information by releasing images of civilian suffering in cities in Iraq subjected to US military action. In The Hunger Games Katniss employs the same concept of images “challenging conventional visualizations” (Kennedy 268) by manipulating the state-controlled media in order to express and disseminate her political dissent.

Despite the inherent violence of its subject matter, The Hunger Games avoids any explicitly graphic or gory images, falling in line with the requirements of the Young Adult genre (rated PG-13). The violence of the Games is conveyed instead through a close visual and emotional alignment with Katniss. Her POV shots, conveyed through hand-held camera and rapid pans, emphasise her frantic struggle, contrasting the Capitol audience’s apathetic response to brutality. As Noah Berlatsky observes, the criticism is not simply directed at the audience within the film, namely the Capitol’s citizens, but also at us, the audience of the film, since “filmgoers watch Katniss fight with the same excitement as do the inhabitants of the Capitol”. In the arena, the sadistic behaviour that mark some of the tributes – Clove, for instance, who wants to torture and disfigure Katniss – align them with the soldiers implicated in Abu Ghraib, whom war has reduced to “sociopaths unable to feel empathy or even recognize the loss of their ethical bearings” (Westwell 154). Katniss, on the contrary, when no ethical choice seems possible, manages to find a way out by saving both Peeta and herself, escaping the ethical labyrinth of violence she finds herself in.

The Hunger Games seems therefore to align itself with a cinematic strand that is “suspicious, resistant and incredibly paranoid” towards US foreign military actions (Westwell 61). The downbeat ending shows President Snow watching Katniss through media surveillance, while she is back in District 12, still living according to his rules. However, as the 2012 film is the first installment of a franchise, such an ending merely sets up a conflict, and its revolutionary potential, to be resolved in the sequels.

Warrior Princess? Marc O’Day argues that, in the context of Hollywood action films, a female protagonist is generally portrayed by “stressing [her] sexuality and availability in conventional feminine terms” (203), thus bringing attention to her male counterpart’s masculinity. Katniss, as the female lead of a dystopian action movie, diverges from this cinematic convention. In fact, she shifts back and forth between traditionally masculine and feminine behaviours. Her father’s death and her mother’s passivity force Katniss to become the primary caregiver for the family. As Berlatsky points out: “Katniss’s feelings for her sister are maternal, but she expresses them most dramatically through being iconically paternal – by going into battle to protect her family”. Katniss’ paternal attitude is juxtaposed with her mother’s and Prim’s more traditionally feminine attitude, as well as by comparison with Peeta. While he is aware of his weaknesses and willing to bargain in order to survive, Katniss is marked by a more determined and often inflexible personality. Furthermore, when Katniss momentarily acquires a more eroticised feminine identity in the Capitol, she is aware of the constructed nature of it, and regards it as a mask she needs to wear in order to meet her goals within the patriarchal consumer culture in which she finds herself .

The main consequence of the televised nature of the Games – a satire of 21st century celebrity culture – is that “appearance is everything” (Frickle 22). The edited clips and images that are broadcast by the Capitol turn the tributes into celebrities or, more to the point, into products of consumption: their private lives are publicly displayed, their stories commercialised, while “new identities are constructed for them” (Fricke 22). Katniss understands that, in order to receive help from the sponsors in the arena, she needs to gain popularity, and therefore she has to actively negotiate her femininity, and perform the new identity that is assigned to her. Crucial elements of this process are costumes, as, in the Capitol, Katniss’s “dresses are a performance. They function as a kind of drag, not an expression of her own gender identity or choices” (Berlatsky). Gender itself becomes a performance whose manufactured nature emerges in the film, as in the sequence in which Katniss is interviewed by Stanley Tucci’s character, Caesar. The back-stage dialogue between Katniss and the stylist Cinna (played by Lenny Kravitz) shows the heroine’s uneasiness in the new eroticised role that has been created for her. When she eventually steps onto the stage, shots of the immense audience produce a sense of anxiety and helplessness, as Katniss feels the pressure of the spectators’ gaze. Here, it is clear how “the tributes’ bodies become mere commodities” (Fricke 23) to be consumed by the audience of the Capitol. Nevertheless, during the interview, the alternation of shots of Katniss, on the one side, and, on the other, of the public, which responds with enthusiasm to Katniss’s presence and words, tracks the character’s gradual (albeit temporary) embrace of her feminine role, climaxing when she stands up and rotates, letting the audience stare at the spectacle of her dress on fire (Butler 2011).

Katniss is not the only strong female character that Jennifer Lawrence has portrayed. Other examples are Mariana in Burning Plain (2008), Ree in Winter’s Bone (2010) and Joy in Joy (2015). Adolescent Ree is particularly reminiscent of Katniss: she is her family’s primary caregiver, as her mother suffers from severe depression, and her meth-addicted father is missing. In this context, just like in The Hunger Games, the disruption of gender stereotypes is linked with the destabilisation of traditional family representations. Significantly, when Ree starts looking for her father, one woman asks her: “don’t you have a man who could do this for you?” to which Ree replies “no, Ma’am I don’t”. Ree’s world is also strikingly similar to Katniss’ District 12: shots of dark log cabins surrounded by the woods, emaciated men and hungry children living in a landscape of bleakness, desolation and fear. Trapped in a net of crime and blood, Ree eventually manages to keep hold of her family home, but the world where she is condemned to live remains identical. The same gloom characterises the aforementioned ending of The Hunger Games, whose pessimism, as Berlatsky suggests, “seems built, in no small part, on the way the series can see no comfortable gender role for its central hero”. Katniss and Ree do not feel comfortable when performing masculine functions and see their actions as mere necessities to survive in a world where the only language is violence. However, “possible alternatives – love, children, even just wearing pretty clothes – are all also viewed with suspicion” (Berlatsky). Such problematic fluidity makes The Hunger Games an unconventional entry within the YA and the action genres, one that challenges stereotypical gender roles in Hollywood movies whilst also showing that films led by a female heroine can be successful even in a male-dominated franchise marketplace.

References

Bauckhage, Tobias. “Social Media Buzz: Young Audiences Focused on ‘Divergent’ at Weekend Box Office.” Variety. 21 Mar. 2014. Web. 8 Dec. 2016.

Berlatsky, Noah. “The Hunger Games World is no Country for Glamorous Women.” The Guardian. 30 Nov. 2015. Web. 11 Nov. 2016.

Butler, J. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. London: Routledge, 2006.

Butler, J. ‘Gender is Burning’. Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex. London: Routledge, 2011 pp. 84–95.

Child, Ben. “Not the Future After All: the Slow Demise of Young Adult Dystopian Sci-fi Films.” The Guardian. 25 Mar. 2016. Web. 7 Nov. 2016.

Driscoll, Catherine. “Introduction – The Adolescent Industry: ‘Teen’ and ‘Film.’” Teen Film: A Critical Introduction. Oxford, New York: Bloomsbury, 2011. 1-8. Print.

Fernandez, Jay A. “’Hunger Games’ Producer Nina Jacobson on Movie Backstory; Firing from Disney.” The Hollywood Reporter. 15 Mar. 2012. Web. 13 Dec. 2016.

Fricke, Stefanie. “’It’s all a big show’: Constructing Identity in Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games Trilogy.” Politics in Fantasy Media: Essays on Ideology and Gender in Fiction, Film, Television and Games. Eds. Gerold Sedlmayr and Nicole Waller. North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2014. 17-30. Print.

Jess-Cooke, Carolyn. “Introduction: The Age of Sequel: Beyond the Profit Principle.” Film Sequels. Edimburgh: Edimburgh University Press, 2009. 1-14. Print.

Kennedy, Liam. “American Ways of Seeing.” American Thought and Culture in the 21st Century. Eds. Martin Halliwell and Catherine Morley. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2008. 259-273. Print.

King, Geoff. “New Hollywood, Version II: Blockbusters and Corporate Hollywood.” New Hollywood Cinema: an Introduction. London: I.B. Tauris & Co, 2002. 49-84. Print.

King, Geoff. “Spectacle, Narrative and the Spectacular Hollywood Blockbuster.” Movie Blockbusters. Ed. Julian Stringer. London and New York: Routledge, 2003. 114-125. Print.

Kowalczyk, Piotr. “Young Adult Books – 10 Most Interesting Infographics and Charts.” Ebook Friendly. 9 Dec. 2016. Web. 16 Dec. 2016.

Miller, Laura. “Fresh Hell: What’s Behind the Boom in Dystopian Fiction for Young Readers?” The New Yorker. 14 Jun. 2010. Web. 7 Nov. 2016.

O’Day, Marc. “Beauty in Motion: Gender, Spectacle and Action Babe Cinema.” Action and Adventure Cinema. Ed. Yvonne Tasker. Oxon: Routledge, 2004. 201-218. Print.

Snow, Nancy. “US Propaganda.” American Thought and Culture in the 21st Century. Eds. Martin Halliwell and Catherine Morley. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2008. 97-111. Print.

Vinjamuri, David. “‘The Hunger Games’: Why Lionsgate Is Smarter Than You.” Forbes. 22 Mar. 2012. Web. 11 Dec. 2016.

Westwell, Guy. Parallel Lines Post-9/11 American Cinema. New York, Chichester: Columbia University Press, 2014. Print.

Whitford, Emma, and Vineyard, Jennifer. “YA by the Numbers.” New York. 6 Oct. 2013. Web. 12 Nov. 2016.

Written by Costanza Casati (2017); edited by Christian Dametto (2019), Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Please obtain permission before redistributing. Selling without prior written consent is prohibited. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2017 Costanza Casati/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post