Plot Bletchley Park, 1939 World War II. MI6 hires Alan Turing and other cryptographers to break the Nazi encryption machine, Enigma, but the machine’s settings are changed every day. Alan designs a machine which will decode any encrypted message, named Christopher, after his only childhood friend. In need of staff, Alan hires Joan Clarke to secretly work on the Enigma mission but Christopher fails to crack the code. Alan confesses to John Cairncross that he has had sexual relations with men but he keeps it a secret, and proposes to Joan. One night, Alan has an epiphany and programs Christopher to search for repeated words in the encrypted letters. They crack the code. However, they cannot act on every attack, as this would raise suspicion. Alan discovers that John is a Soviet spy and learns that MI6 intentionally hired him to leak information to Stalin. In fear that Joan’s secret involvement with the group will get her into trouble, Alan calls off their engagement. Once Britain wins the war, the group burn all traces of their work and return to their former lives. Manchester, 1951. Following a burgarly, Detective Nock suspects Alan of being a Soviet spy. However, the burglar is, in fact, a homosexual prostitute who Alan hired. Alan is charged with gross indecency and undergoes chemical castration. Ultimately, he is left with only Christopher by his side.

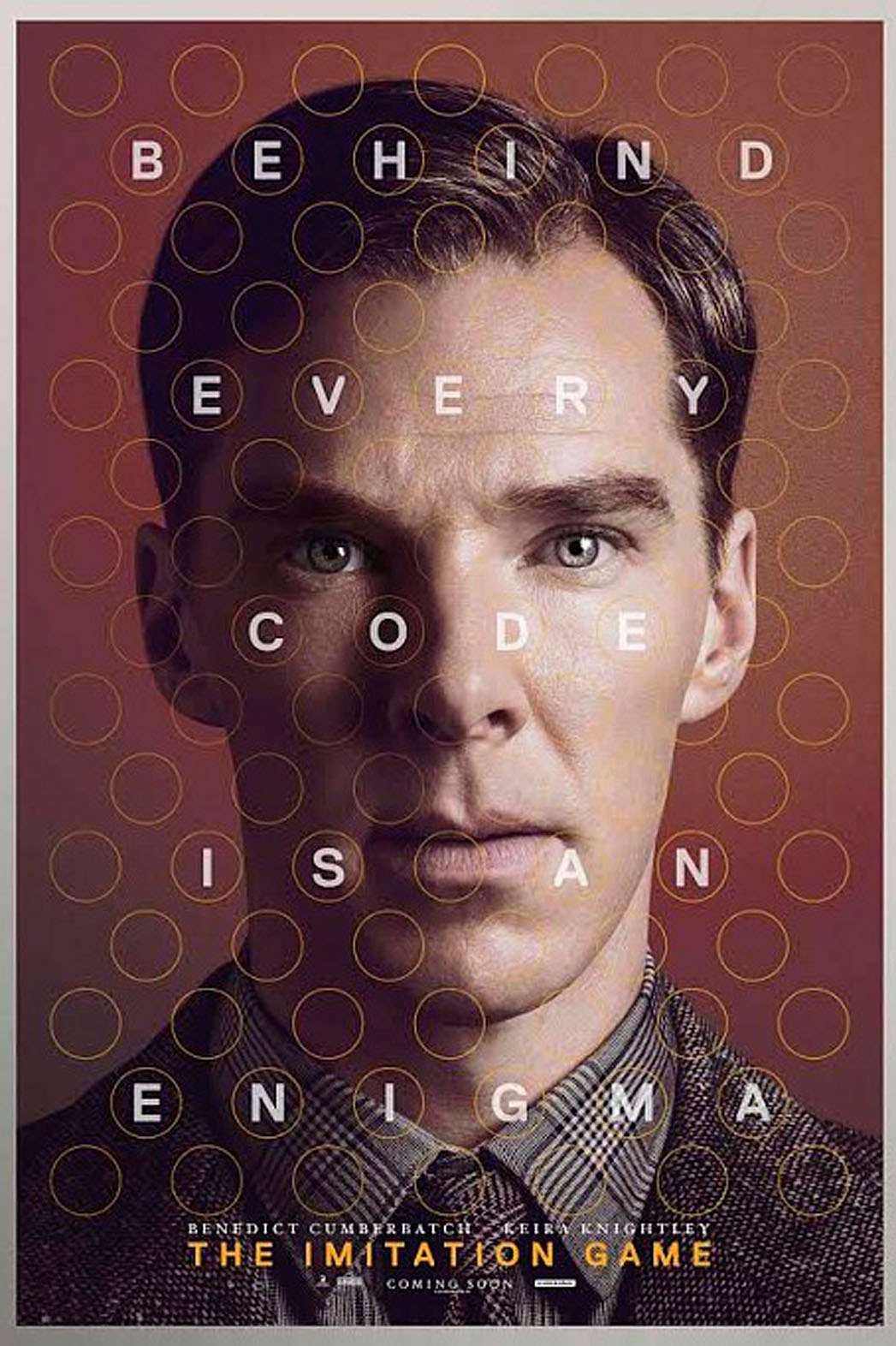

Film note Hollywood studios often favour films which have the key ingredient of familiarity because there will be a higher chance of box office success. Lynda Obst (producer of Interstellar (2014)) asserts that in Hollywood, familiarity breeds success, not contempt” (Garrahan) and this is evident in the recurrence of franchises, film adaptations, sequels, and prequels. Morten Tyldum’s The Imitation Game (2014) is distinctive in its lack of familiarity. This made the film a financial risk to produce and promote but it still achieved an impressive worldwide box office gross of $233.6m.

An unfamiliar film The Imitation Game’s production company, Bristol Automotive, was established by first time producers, Ido Ostrowsky and Nora Grossman. They were fortunate enough to have Graham Moore write the film screenplay based on Andrew Hodges’ novel Alan Turing: The Enigma (1983), because “no one else was knocking on [their] door” (Siegel). The producers also teamed up with Teddy Schwarzman from Black Bear Pictures, who found that The Imitation Game “would fit perfectly into Black Bear’s canon: original, engaging and complex character-driven characters such as their recently claimed All Is Lost, starring Robert Redford” (Production Notes). Being the son of billionaire Stephen Schwarzman, Schwarzman was certainly not short of money, and was so “blown away by Moore’s screenplay” that he was able and “willing to greenlight the film without a [calibre] star” (Siegel).

It was precisely Moore’s screenplay which attracted producers and actors to the project because it topped the annual blacklist for December 2011. The annual blacklist is a survey for the “most liked” but unproduced picture, as voted by studio executives. Initially, Warner Bros. showed interest in the film, accompanied by rumours of Leonardo DiCaprio for the lead role (Kit & Siegel). Following the collapse of this potential collaboration, The Weinstein Company purchased the rights to the screenplay for a record $7m, even without the guarantee of a Hollywood star. For the lead role, Benedict Cumberbatch was ultimately selected by the production team because of the “mix of sensitivity and strength” in his acting which “could synthesise Turing’s genius, his humanity and myriad complexities” (Production Notes). Though Cumberbatch had already “expressed interest when the project was at Warners”, the studio “didn’t consider him a big enough star” (Siegel). Nevertheless, Cumberbatch has earned “an avid fanbase of women and gay men” (Lang), many who have followed him since his casting as Sherlock Holmes in the internationally-successful British TV series Sherlock (2010-ongoing). Many critics have even drawn parallels between Cumberbatch’s characterisation of Turing and that of Sherlock, since both characters are socially awkward, arrogant geniuses. In Hollywood, Cumberbatch has established his reputation with films such as 12 Years a Slave (2013), Star Trek into Darkness (2013) and Doctor Strange (2016).

In previous examples of biopics, there is a tendency to share stories of recognisable public figures, often “a monarch, political leader, or artist” (Kuhn & Westwell, 32). In these films public ‘pre-awareness’ of the lives of significant figures enhances the appeal. The Imitation Game, on the other hand, centres on the unknown figure of Alan Turing, whose accomplishments during World War II were kept classified by MI6, and only later revealed through letters and Andrew Hodges’ biography. Although there have been attempts to bring Turing to screens, including the television shows, Breaking the Code (1996) and Codebreaker (2011), and the feature films, Enigma (2001) and The Turing Enigma (2011), these failed to reach a mass audience. Tyldum’s film is not the first example of converting an unfamiliar figure into the protagonist of a biopic. In 2013, The Wolf of Wall Street was released, based on the true but not widely known story of Jordan Belfort. Instead of selling “these specific people’s lives”, it is about “selling the biopic itself… that tells us we’re going to see Something Grand, Important, Entertaining, and Transporting” (Ebiri). What attracted the production team to Turing’s story was the combination of an inspiration war genius and his tragic prosecution for homosexuality, rendering it “a story that the world needed to hear” (Production Notes).

Alongside The Imitation Game, many other biopics were nominated for the 2015 Academy Awards such as American Sniper (2014), Selma (2014) and The Theory of Everything (2014). American Sniper even managed to gross the highest box office of 2014, surpassing The Hunger Games: Mockingjay Part 1 which incorporates as much familiarity as possible through the book and film franchise. Arguably, “truly great biopics find a way to reinvent the form” (Ebiri) which The Imitation Game attempts to do by attaching the thriller sub-genre to it. Dan Jolin claimed that the film “isn’t such a crazily far cry from the murky, pacy Headhunters” (2013), a well-received Norwegian thriller also directed by Tyldum. Despite Tyldum’s unfamiliarity among American audiences, The Weinstein Co. exploited his foreignness by ensuring that he mentioned it as a “clear talking [point] during every interview, Q&A and acceptance speech” (Feinberg), so that the “outsider status of his own role” (Production Notes), coincided with Turing’s outsider status at Bletchley Park. In spite of the audience’s unfamiliarity with Tyldum, as well as the other aspects of unfamiliarity, the production team for The Imitation Game should be applauded for their development of a film that pays “homage to an extraordinary life while honouring the tale’s most challenging and unique elements” (Production Notes). Overall, Bristol Automotive and Black Bear Pictures succeeded in producing a novel and unfamiliar yet inspiring and commercially successful film.

Oscar-bait Within Hollywood exists a hybrid category known as Indiewood – a combination of independent cinema and Hollywood. These kinds of films aim to “either to supply demand that the (major) studios cannot meet or to cater for niche markets” (Kuhn & Westwell, 226). Following this definition, The Weinstein Company operates with the former in mind. Unlike the novice producers of The Imitation Game, Harvey and Bob Weinstein are experienced in film distribution, working the field since 1979, when they co-founded Miramax. After leaving Miramax in 2005, the Weinsteins founded The Weinstein Company. The King’s Speech (2010), also distributed by the Weinstein Company, accumulated a successful domestic gross of $138.8m. As a result, the Weinstein Company took to imitating its method of distribution for The Imitation Game. From this release, The Imitation Game earned a total of $482,000 from four theatres in New York and Los Angeles. This opening weekend exceeded The King’s Speech’s, which earned $355,000 from the equivalent number of screens. As Phil Contrino notes, the Weinsteins are “masters at starting slow and making sure they build momentum” (2014). Gradually, The Imitation Game expanded to more screens and reached a nationwide release by Christmas Day.

Besides the release strategy, Indiewood distributors acknowledge the significance of the Academy Awards in raising awareness and publicity for their films. Winning an Oscar, especially in categories such as Best Picture, Best Actor and Best Actress, can provide “a big boost in international box office because they mostly premiere overseas later allowing them to capitalise on awards” (Marich 174). Accordingly, the Weinsteins work hard to promote their films to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. As a consequence, their films typically become Oscar contenders. In the lead up to the Academy Awards, “for your consideration” advertising is directly aimed at voting members of the academy. The Imitation Game’s press focused on Alan Turing and his wartime achievements, and his contribution to the development of computer technology. The campaign also mentioned Turing’s tragic suicide. The text reads “all these years the injustice remains”, spurring the members to vote for the film as a way of honouring Turing. Consequently, the advertising “started to resemble an expensive political campaign” (Balio 136).

The campaign also included the likes of Google executive chairman Eric E. Schmidt, Twitter CEO and Director Dick Costolo and Paypal co-founder Max Levchin. Repeatedly referred to as the “father of computers” by several critics, Schmidt declared that “Alan discovered intelligence in computers, and today he surrounds us”. By tapping into the contemporary digital age, The Imitation Game extends beyond “older, sophisticated audiences […] because of the nature of the film” and appeals to younger audiences and tech heads (Lang). In an attempt to attract queer audiences and those in support of LGBT rights, Weinstein also emphasized the topic of homosexuality. Despite Turing’s posthumous royal pardon in 2013, Weinstein decided to generate a movement to have Turing “honoured by the British government”, as well as “[pardoning] the thousands of British citizens convicted under laws forbidding homosexuality”. His act for social progress encouraged others to join him, including actor Stephen Fry and a Washington-based human rights campaign (Kilday). Through the movement, Weinstein abided by the campaign’s tagline “Honour the man. Honour the film”. It would certainly not be the first instance The Weinstein Company have used this technique: for example, Weinstein “sent the Silver Linings Playbook team to Congress to lobby on behalf of mental health legislation” (Kilday). Both examples demonstrate how the Weinsteins are skilled at turning an Academy Award campaign into a political matter, thereby ensuring maximum publicity and dividends at the box office.

Turing’s sexuality Following the disintegration of classical Hollywood’s Production Code, there was a noticeable rise in queer characters and relationships in film. Historical events such as the 1960s Stonewall Riots and the AIDs crisis during the 1980s, led to the discussion of queer theory in film studies. It also resulted in the advent of New Queer Cinema in the early 1990s, which originated from independent cinema but soon after entered “mainstream gay Indiewood” because “of a neoliberal hegemony embracing independent queer film” (Richards 21). For example, Brokeback Mountain (2005) was a game changer for New Queer Cinema because it brought a homosexual relationship between two major Hollywood male leads and an intense gay sex scene in a tent to mainstream Hollywood cinema. Considered by some to be part of this New Queer Cinema cycle, LGBT groups were eager and willing to commend The Imitation Game for the portrayal of its homosexual lead character. The Imitation Game was given a GLAAD Media Award for Outstanding Film. GLAAD advocates for positive depictions of queer characters, with CEO Sarah Kate Ellis remarking that it is a “struggle to find [queer] depictions anywhere near as authentic or meaningful in mainstream Hollywood film” (Lee). The most probable reason for The Imitation Game winning the GLAAD award is because “Turing has rightly become a martyr for LGBT rights” (Walters). Ben Walters comments that The Imitation Game “could be the queerest thing to hit the multiplex in ages”(2014).

However, films from the classical Hollywood era were forbidden from displaying an “explicit representation of “sex perversion”” and restricted from “depicting homosexuality in a forthright manner” (Benshoff & Griffin, 7) and some critics reprimanded The Imitation Game for its lack of gay sex scenes and/or depiction of a clear homosexual romantic relationship between Turing and another man. In response, Tyldum defended his decision to omit any scenes of homosexual sex, arguing that they would betray the characterisation of Turing. He explains that Turing’s “whole relationship, how he falls in love and the importance of him being a gay man, was all about secrecy” (Walters). When the onscreen treatment of homosexuality was finally allowed from 1961 it was under the condition that homosexual characters had to be judged negatively. This paradigm can still be identified in contemporary films which “routinely implied that queer lives were empty, lonely, pitiful, and all too often deadly” (Benshoff & Griffin, 8). This is evident in The Imitation Game where Turing is forced to undergo chemical castration to ‘cure’ himself of his homosexuality, only then to commit suicide. The implication that homosexuality ends in tragedy may also be associated with Christopher, Turing’s crush, who passes away from tuberculosis.

The cinematography follows this logic, especially in the way it articulates the segregation between the homosexual Turing and the rest of the heterosexual team in Hut 8. In the scene where Cairncross invites Turing for lunch with the group, the shot reverse shot keeps the two characters in isolated, separate frames. Even in the wide shots, Turing is either placed at a distance or literally stands in opposition to the group. This oppositional logic is displayed in the scene where Turing is accused of being a Soviet spy by Commander Denniston, ending in a wide shot of Turing on the left hand side of the frame and the others on the right. It is only because of his otherness that he is suspected of a crime, which foreshadows his later incrimination for his homosexual activity. The Imitation Game cannot be regarded the “queerest thing”, for it maintains rather than “[deconstructs] simple straight-gay binaries” (Kuhn & Westwell, 289). In the film, once it is announced that Turing and Joan Clarke are engaged, he is finally assimilated into the group. This leads to a shift in the cinematography which features more wide shots with Turing in frame and in proximity with the rest of the group. Consequently, the film reinforces the ““normal” orientation of male-female attraction and desire, while homosexuality remained its “abnormal” shadow” (Benshoff & Griffin, 3).

Because The Imitation Game downplays Turing’s sexuality, only referring to it as a subplot, The Weinstein Company were able to promote the film to “a mass public beyond queer niche audiences” (Richards 20). In keeping with this construct, The Imitation Game privileges Turing’s relationship with Clarke. By neglecting any form of a homosexual relationship, excluding Turing’s schoolboy crush on Christopher, the film is guilty of ‘straightwashing’. In a bid to please mass and conservative audiences, “queerness becomes the very liability for [the film] to overcome” (Richards 20). At Bletchley Park, Turing doesn’t seem to pay women any attention, but with that being said, he doesn’t seem to pay men any attention either. There is the suggestion that he is asexual rather than homosexual.

Other factors which make “Indiewood films with LGBT themes” easier for mass audiences to watch is to have it “set in the past”, making it “[feel] more like a history lesson than a participation in gay cinema” (Richards, 25). The Imitation Game educates audiences about the history of World War II and how Turing assisted in ending the war along with a group of mathematicians. This could explain why the film concentrates more on the mission to decode the Enigma machine, instead of exploring Turing’s personal love life. By placing characters “in environments where queer sexuality is abnormal and socially undesirable”, it creates enough discrepancy between the past and “our current cultural condition” (Richards, 25). In the 21st century, queer sexuality is more openly and legally accepted such as with the introduction of same-sex marriage in certain states. The disparity between past and present enhances The Imitation Game’s crossover appeal and demonstrates that heterosexuality perseveres as the dominant sexuality in Hollywood cinema. While Benedict Cumberbatch notes that “human rights movements and sexual and gay rights movements have made huge social progress in the last 40 years” (Child), the same cannot be said of mainstream cinema, which has made far slower progress.

References

Benshoff, Harry M., and Sean Griffin. Queer Cinema: The Film Reader. Routledge: New York, 2004.

Child, Ben. “Benedict Cumberbatch: I’d defend gay rights ‘to the death’”. TheGuardian.com. 15 Oct. 2014. Web. 5 Nov. 2016.

Ebiri, Bilge. “Hollywood, For the Sake of Biopics, Stop Making So Many Biopics”. Vulture.com. 20 Feb. 2015. Web. 20 Nov. 2016.

Eisenberg, Eric. “The King’s Speech is only a frontrunner because it’s manufactured Oscar Bait”. Cinemablend.com. 2011. Web. 16 Nov. 2016.

Feinberg, Scott. “How the Weinstein Co. Turned ‘Imitation Game’ Director into an Oscar Contender”. Hollywoodreporter.com. 8 Jan. 2015. Web. 20 Nov. 2016.

Garrahan, Matthew. “The rise and rise of the Hollywood Film Franchise”. Ft.com. 12 Dec. 2014. Web. 5 Nov. 2016.

Gray, Tim. “How ‘Sniper’, ‘Imitation Game’ and ‘Selma’ made a difference beyond Oscar race. Variety.com. 20 Feb. 2015. Web. 20 Nov. 2016.

Jolin, Dan. “The Imitation Game Review”. Empireonline.com. 27 Nov. 2013. Web. 27 Oct. 2016.

Kilday, Gregg. “Oscars: ‘The Imitation Game’ finally plays the gay card”. Hollywoodreporter.com. 29 Jan 2015. Web. 8 Nov. 2016.

Kit, Borys and Siegel, Tatiana. “Warner Bros. Is Letting Go of ‘Imitation Game’”. Hollywoodreporter.com. 17 Oct. 2012. Web. 24 Oct. 2016.

Kuhn, Annette, and Guy Westwell. A Dictionary of Film Studies. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2012.

Lang, Brent. “’Imitation Game’ Scores Huge Debut Thanks to Oscar Buzz, Benedict Cumberbatch”. Variety.com. 30 Nov. 2014. Web. 12 Nov. 2016.

Lee, Benjamin. “Gay audiences are still short-changed by Hollywood, Glaad survey suggests”. Theguardian.com. 16 Apr. 2015. Web. 27 Oct. 2016.

Marich, Robert. Marketing to Moviegoers: A Handbook of Strategies and Tactics. Southern Illinois University Press: Carbondale, 2009.

“Production Notes: The Imitation Game.” Twcpublicity.com. Web. 20 Nov. 2016.

Richards, Stuart. 2016. “Overcoming the Stigma: The Queer Denial of Indiewood”. Journal of Film and Video 68 (1): 19-30.

Schwarz, Hunter. “‘The Imitation Game’ isn’t really about Gay Rights. But its Oscars Campaign is”. TheWashingtonPost.com. 21 Feb. 2015. Web. 8 Nov. 2016.

Siegel, Tatiana. “Cracking the Code: How Two Out-of-Work Producers Brought ‘Imitation Game’ to the Screen”. Hollywoodreporter.com. 11 Nov. 2014. Web. 8 Nov. 2016.

Walters, Ben. “The Imitation Game: The Queerest Thing to Hit Multiplexes for Years?” The Guardian.com. 9 Oct. 2014. Web. 8 Nov. 2016.

Written by Casey Wong (2016); edited by Guy Westwell (2017), Queen Mary, University of London

This article may be used free of charge. Selling without prior written consent prohibited. Please obtain permission before redistributing. In all cases this notice must remain intact.

Copyright © 2017 Casey Wong/Mapping Contemporary Cinema

Print This Post

Print This Post